Troubled Times Reveal The Value of Resilience, Explains James Atkins, Chairman of Vertis Environmental Finance

By Jacob Doyle

With our existence on this planet becoming increasingly uncertain and unstable, we need to start learning about resilience. This is the position put forward by ecologist and investor James Atkins in his recent essay, Bouncy castles or potatoes? What we are learning about resilience, efficiency, and risk management.

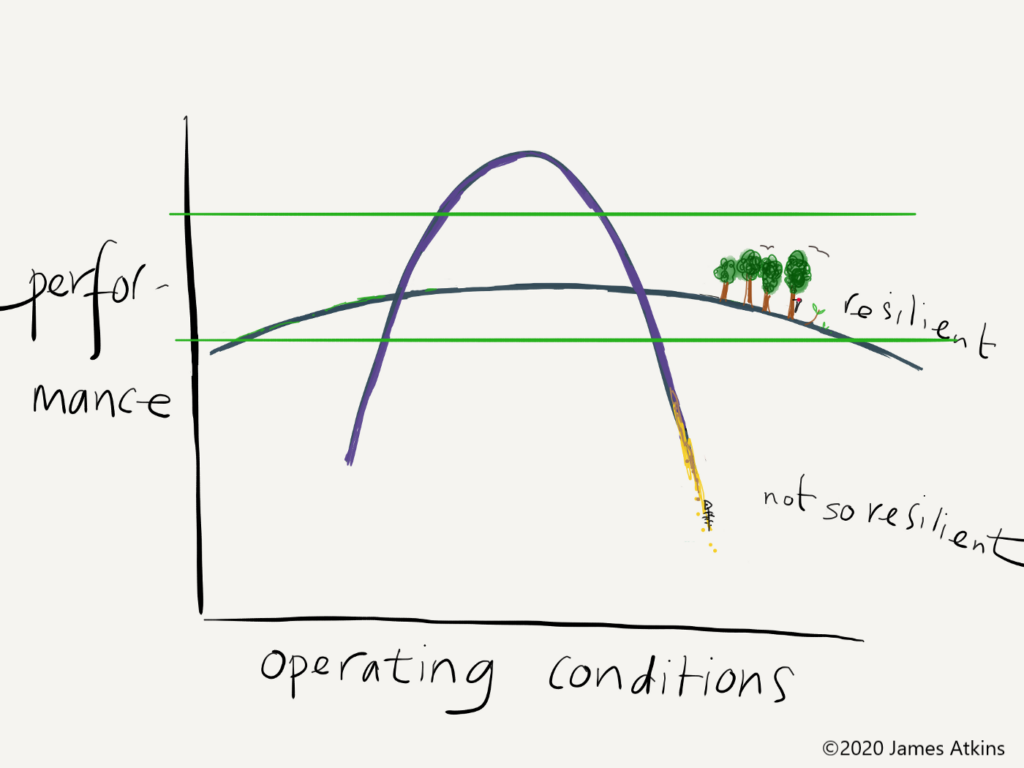

Resilience measures the range of “operating conditions” within which a given system can function at an acceptable level, Atkins explains, and includes some graphic illustrations for the right-brained among us.

“Things start to break down under catastrophe,” Atkins writes, in a clear allusion to our current pandemic. “This means that an intolerable number of people suffer unacceptably. It seems that we have a standard of what is an acceptable and what is an unacceptable level of disruption to people. And when that level of disruption is reached, that is the signal that our system is not managing, and then prompts thoughts that we are not resilient enough.”

Building and investing in resilience when times are good will keep things running well enough when times turn bad, whether a catastrophe hits, or just a recession. Almost everything needs a dose of resilience, he informs us, “anything which can be threatened with being broken.” Our homes, farms, bodies, bridges, energy grids, our economies; he mentions them all.

Resilience can be passive or active or systemic.

In passive resilience, a favorite of policy-makers, “you have a low-intelligence system which is set up at the beginning and does not need a lot of maintenance. Sea defence walls, very strong safes, high levels of regulatory capital or inventory are in this category.”

Less favored by policy-makers is active resilience, “an intelligent system which adapts to the threat and can change its form of operation to become safe under the threat,” because of its expensive need for regular maintenance, its complexity, and the fact that it’s so rarely used. Examples include emergency response systems.

Systemic resilience involves a complex system which is resilient throughout, such as a market, an ecosystem or a living body.

Justifying the expense of any one of the three can be helped by quantifying its effectiveness. Quantification is more complex for resilience than for efficiency, which is basically performance over cost. To clarify how this quantification could work, Atkins gives the example of a motor’s varied performance at different temperatures.

“You have a number for the efficiency of the system at each level of operating conditions. So instead of saying ‘this motor has an efficiency of 28%,’ you have to say ‘this motor has an efficiency of 28% in a temperature range of 10°C and 30°C, and of 24% in a temperature range of 30°C to 40°C and 20% in a temperature range of 40°C to 50°C.”

The wider the range of temperatures under which the motor can operate at acceptable efficiency, the higher its resiliency rating would be.

When the system being discussed is the well-being of humanity, expectations for resilience are currently very high. A pandemic which wipes out 10% of a termite colony would likely just see the surviving 90% get on with business. When, however, such decimation threatens us, we’re horrified, as we now know too well.

Atkins mentions four factors currently weakening our capacity for resilience to extreme threats:

- The lack of basic skills in urban populations is a huge vulnerability, e.g. cooking, gardening, plumbing, etc;

- Not enough “truth” – people are too quick to believe what they want to hear from others who are too willing to feed it to them, regardless of its veracity;

- Too many countries depend too much on importing vital things;

- We depend too much on a very small number of commercially bred crops.

He drills down further by posing “five big questions” related specifically to our resilience to the current pandemic.

With the first – “Why isn’t China right?”- he parallels China’s steadfast action in containing the virus’ spread with its government’s totalitarian rule. The wrong lesson to learn would be that to achieve resilience against a pandemic, we need to say goodbye to liberal democracy. A better example to follow could perhaps be South Korea, which has also managed to contain its own initially severe outbreak, but under the leadership of a democratically-elected center-left President Moon Jae-in.

The second question asks about resilience in the face of climate change and the loss of biodiversity. Resilience here could be gained by doing the following:

- Make farming more resilient: regenerative-organic farming, agro-forestry and permaculture

- Restore hundreds of millions of hectares of forest, wetland, grassland, etc.

- Make food production more diverse, less dense, with shorter, more robust supply chains

- Become trained and agile in switching operating modes, e.g. from “normal” to “pandemic response”

- Have more financial and physical capital tied up in reserve

- Learn to handle mass migrations of people displaced by disasters, wars, etc.

- (Re)construct resilient buildings to save energy and handle extremes of temperature

Question number three challenges us to redefine our current acceptable performance levels, shifting away from levels of GDP growth to considerations of what performance should be expected in “normal” circumstances and what could be the minimum performance level expected for difficult times.

Four asks us what the current pandemic disruption can teach us about resilience. It focuses on how clear it has become how damaging “normal” life is to the natural environment now that the skies are clear with cars off the road and factories on hold. Practising resilience by hitting the pause button can have enormous benefits for mental and physical health, too.

The final question asks “Can we improve resilience without compromising on performance?” and answers, “yes, and in some vital ways.”

By broadening performance measures to take account for externalized costs and benefits and adjusting time horizons, resilience is revealed to be the best friend of performance. Sustainable farming proves to be more cost-effective in the long-run than its industrial agriculture cousin, with its depleted soil, subsidies and poisonous chemicals.

Atkins concludes by reflecting the COVID19 pandemic, its ramifications and the world’s response. He raises the spectre of future crises of global impact, the rapidly changing climate in particular.

“In order to get fresh answers, we should think more about resilience,” he says. “This includes how we operate, the range of operating conditions we want to be resilient to, the expected and acceptable performance levels under normal conditions, the measures of performance, the resilience measures to be taken, and the modus operandi under those measures. I think if we make a very rigorous and thorough examination, we will discover additional arguments for speeding up transformation to a more sustainable and compassionate society.”